On a Sunday morning in late April 2018, I received a text from one of my husband’s few female cousins: “Auntie Shirley is at church and she’s had an accident. She needs help in the bathroom. I can’t go and neither can Mom. Debby, do you think you can help?”

I was on my way to Hebrew school to teach music. Also, I’d long ago vowed that I was never going to clean the bum of any adult to whom I was not related by blood, but an emergency is an emergency, and I didn’t want to leave 82-year-old Auntie Shirley stranded and uncomfortable. Plus, we live right across the street from the church. I hurried, mindful that Shirley was alone in the bathroom, no doubt a mess, both literally and figuratively.

I didn’t know Shirley well. She had only moved to Edmonton recently. For most of my marriage to Dave, she’d lived either in Calgary (three hours away) or on Vancouver Island (a 12-hour drive followed by a ferry ride). The times I’d met her she’d always been pleasant, but I dreaded having to be that intimate with someone I barely knew. I imagined finding her in the bathroom, morose and needy. So I was quite surprised when I arrived at the church and there she was, on a bench in the lobby with a smile on her face, not looking at all like someone who needed an adult diaper change.

“I thought you had an accident,” I said.

“I did,” she said. “But I didn’t want you to have to come looking for me.”

Into the bathroom we went. I’ll spare you the details. Suffice it to say, it was neither a pretty task, nor a clean one. But what made the event less awful than it could have been—indeed, what made it delightfully memorable—was when, as I was bent over her back, scrubbing her tush, Shirley said, quite brightly, “You’re seeing a whole different side of me!” That sure broke the ice. The two of us burst out laughing, I finished cleaning her up, and then my son and one of his cousins helped her into the sanctuary for the Sunday service.

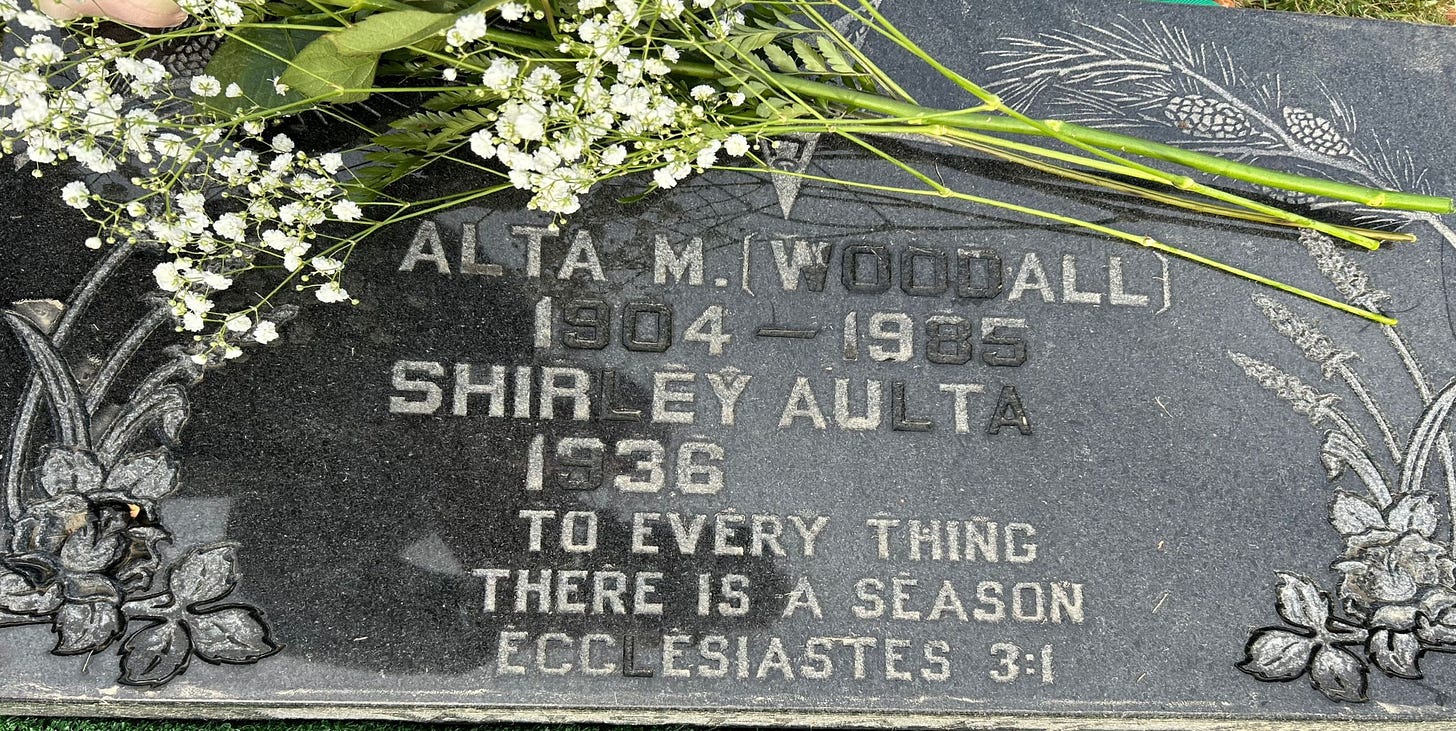

I’d forgotten that story until this week, when more than a dozen of Shirley’s relatives, including her brother (my father-in-law) gathered to bury her next to her parents. After the service, on a sunny day at a beautiful cemetery in Calgary, we went to a restaurant and told stories, many of which featured examples of Shirley’s sense of humor.

Cousin Heather’s husband, Justin, remembered when Shirley moved in with his family in 2016 after she’d been in a car accident and Heather was expressing her frustration that her grandfather, Vern, a retired minister, was against gay marriage.

I figured Justin was going to say that Shirley, who had just turned 80 at the time, placated Heather and told her that she, too, was against gay marriage, and that Heather should respect her grandfather’s beliefs. Was I ever wrong.

As Justin recalled, Shirley was even more frustrated than her great-niece. “Is he still going on about that?” she asked indignantly. “I think I’m going to tell him I’m gay!”

The story made everyone laugh out loud. Who knows? Maybe Shirley had been gay. She never married—though Heather’s mom, Beth, recalls that she had boyfriends. She never graduated from college, either, which must have really frustrated her: she was sharp and intelligent and a gifted visual artist. Had she been born in 1966 and not 1936, she doubtless would have sailed through with a degree in art or history or both, but her brothers were the ones who got to earn advanced degrees.

Shirley became a medical records librarian. Her real passion, though, was geneaology. Upon discovering in 1965 that her father’s parents were Metís who had settled the tiny town of Rosebud, Alberta in the late 1800s, she went on a lifelong quest to learn as much as she could about her family history. That quest took her to the Hudson’s Bay archives in Winnipeg and to the Orkney Islands in Scotland, where she traced the footsteps of Wishart family ancestor James Spence, who was born there in 1754.

At the age of 19, Spence sailed to North America to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company as a skilled boatman ferrying fur traders up and down the North Saskatchewan River. Eight years later he married a “country wife,” the daughter of an English fur trader and his Cree wife.

By the time Shirley and her brothers were born in the 1920s and 30s, their father, Roy, had long learned to keep his Metís heritage a secret. But the work that Shirley and, eventually, Vern did to uncover their family history has had a profound effect on everyone in the family. Inspired by Shirley’s research, Vern wrote two books, a memoir called What lies Behind the Picture: A Personal Journey into Cree Ancestry, and Kisiskaciwan (Saskatchewan): Tracing My Grandmother’s Foot Steps.

Dave’s cousin Beth, a filmmaker, has made moving documentaries about native and Metís culture. One of my favorites is Lana Gets Her Talk, about a local artist, Lana Whiskeyjack. One of her sons, Matt Mackenzie, has written plays inspired by his the family’s newly discovered heritage. I’m a big fan of the most recent one, The First Metís Man of Odesa, a terrific autobiographical play about how Matt came to marry his wife, Mariya, an actress from Ukraine.

Dave, who has started Indigenous training initiatives in bioinformatics and natural product chemistry (e.g., native medicinal cures) at the University of Alberta, where he is a Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, wrote a moving eulogy for Shirley. I’m going to share it here, to give you a sense of the impact Shirley had on her family:

Memories of Shirley Wishart

2024 has been a year of loss for many of us, as we have had to say goodbye to all of the elder Wishart women. Pat, Jo, Shirley – sisters, sisters-in-law, mothers, grandmothers, aunts and great aunts to all of us. The Wishart clan, which has always been small, has now gotten much smaller. It falls to those of us who remain to pick up the mantles of these single and singular sisters and carry their gifts of love, laughter and family lore to the next generations.

Shirley wore many hats in life: she was an astonishingly gifted painter and sculptor, a carpenter, a poet, a traveler, the family photographer, a genealogist and the keeper of our family’s written and oral records. It was through Shirley’s tireless efforts that all of us discovered our own heritage and our deep roots to Alberta, to Canada and to the Indigenous and Metís community that our ancestors had once tried to leave behind. As Beth said, Shirley really found our family. We owe a great debt of gratitude to Shirley's love of history and love of family. She made us proud, especially her brothers, nieces, nephews, great nieces and great nephews to call ourselves Metís and to be part of the historic Red River community. As Shirley was our family’s bard, I thought it would be appropriate to close my remarks with a short poem

Shirley painted memories and penned our song

She turned our gaze towards where we belong

The family artist, poet and guide

Through her, our history lives with pride

Thank you Shirley, we’ll miss you.

Just so lovely!

Lovely, Debby. Thank you.