I’ve been thinking about mentors lately, partly of Rona Maynard’s May 25 Substack about her mentor, partly because I’ve become one, and partly because yesterday was Father’s Day and the mentor who had the greatest impact on me was also something of a father figure. His name was Bill Breisky and I met him in the summer of 1979 when I was hired to be a proofreader at the Cape Cod Times.

I was 18 years old, fresh out of my first year in journalism school at Syracuse University. I already had a job, as a cleaner, dishwasher, and busgirl at the Mattakeese Wharf, a seafood restaurant in picturesque Barnstable Harbor. My friend Lisa’s dad, an advertising salesman at the paper, thought the proofreading gig was a better opportunity.

“It’s a foot in the door,” he said, which I imagine is the sort of thing my own dad, also a journalism school graduate, might have told me if he hadn’t died four years earlier.

I didn't have any contact with Mr. Breisky — I was hired by the managing editor — but about a week after I began working at the paper, he summoned me to his office to talk. I have a vague recollection that he gave me a test of some sort. Typing? Writing? Editing? I can’t remember, only that I passed.

Mr. B. was around my dad’s age, and he was kind and gentle, but I was still intimidated to be in his office. It wasn’t just that he was the editor of a newspaper, which meant he was the kind of person who would someday — perhaps even at that very minute — have the power to make or break my career. Although I couldn’t have articulated as much back then, when I had yet to make sense of my father’s sudden and inexplicable death, I often felt unsettled around men who were of Dad’s vintage.

What I now understand is that in some very deep, unreachable part of my subconscious, I looked at every man born in the late 1920s and early 1930s as a potential father figure. It wasn’t enough to impress Mr. B. with my journalistic acumen: I needed to convince him that I was a daughter worth sticking around for, something I had clearly failed at with my own father.

My dad had studied journalism at Northeastern University, across town from where he’d grown up in Boston. Mr. B. was a Syracuse grad, which is another reason he took an interest in me. After I passed the test he’d administered, he introduced me to Peggy, a nurturing features editor. For the rest of the summer, after I finished my proofreading shifts, she kept me busy writing wedding announcements and briefs for the weekend guide magazine.

Over the next three years, Mr. B. saw to it that I got more and more work at the Cape Cod Times. I covered summer stock theatre press conferences, interviewing the likes of Larry Hagman, John Ritter, and Richard Thomas. For someone as star struck as I, it was a dream gig. At a press conference for an Osmond Family show at the Cape Cod Melody Tent in Hyannis, Marie was ahead of me in the buffet line and served me a cup of clam chowder. I still consider it a career highlight.

Mr. B. and his wife, Barbara, had a son and two daughters, whom I met at the annual summer party they hosted for the staff and their families. Eventually I became friendly with the Breisky daughters independently of Mr. B. When my mother retired and moved to the Cape full time in 1983, she, also a Syracuse grad, began socializing with Mr. and Mrs. B.

I wasn’t the only reporter Mr. B. treated like family: he established close, mentoring relationships with a lot of the writers on his staff. I can’t remember how old I was when I learned that he, too, had lost a parent young — he was six when his mother died. I suspect that gave him one more reason to connect with me.

Mr. B’s endorsement helped me to land my first full-time job, at the daily paper in Concord, New Hampshire. I was hired to cover high school football, a position for which I was ill-suited: I was great at writing sports features but I didn’t know what a touchdown was and I didn’t really care, which proved to be something of a problem when it came to writing game stories.

Eight months into my tenure, the editor, Mike, moved me to the newsroom, put me on probation and gave me a month to prove I was more adept at writing factually accurate news stories than I was at writing game stories. I was mortified (I knew I was a terrible sportswriter) and furious (I also knew I was a good news and feature writer).

Unbeknownst to me, Mr. B. continued looking out for me. All those New England newspaper editors knew each other and he called Mike to monitor my progress. He knew, two weeks before I did, that I was not going to be fired after all, something he didn’t share with me until many years later.

I left New Hampshire of my own accord for a feature writing job at the New Haven Register in Connecticut at the end of 1984, after spending more than two years in the Live Free or Die state. When the assistant features editor at the Register misspelled my name as “Debbie” in my first byline, I called Mr. B. and told him I wanted to quit. I sobbed into the phone, telling him I’d made the biggest mistake of my life, taking a job at a paper where my own editor couldn’t spell my name.

Mr. B. listened patiently and assured me that everyone made mistakes. He was gracious enough not to point out the obvious: that I, of all people, should have understood that, seeing as how I’d almost been fired for just that reason. At any rate, the pep talk worked. I stayed in New Haven for nearly four years, long enough to meet my future husband. Mr. B. gave the toast at our wedding. His daughter, Gretchen, sourced the silk for my dress.

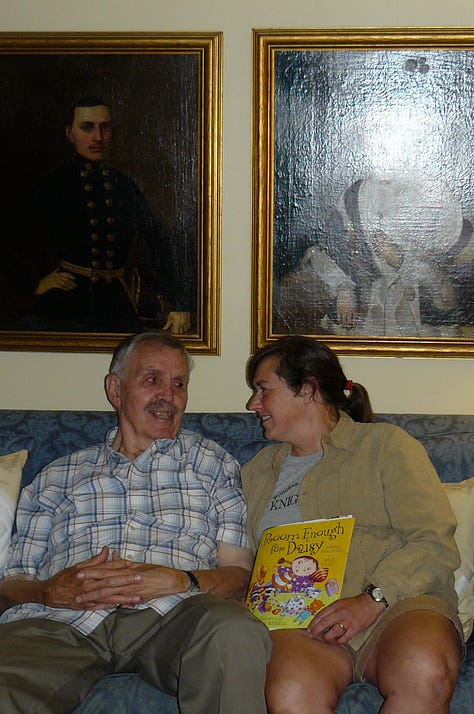

As Mr. B. and I got older, our relationship changed: I began calling him Bill, for one thing. He was still my mentor, but now he shared his work with me so that I could give him feedback. (Here’s a wonderful essay he wrote for the New York Times.) In that sense, we were equals, but I never stopped looking up to him. He died of Covid in January 2021, six weeks after his older daughter, my friend Karen, died from the same virus.

I have yet to find words to adequately express how that loss affected everyone who knew and loved the two of them. One thing I know is that it has strengthened my relationship with Gretchen, whom I consider my sister.

Bill’s consideration and care for me, and above all, his belief in me, had a profound and positive impact on my life. After my dad died, there were other men who tried to step into the breach — my mother’s brother was one, as was a neighbor who taught me to drive, and a member of our synagogue who had been a mentor to Dad — but Bill was the one I connected with. He appeared at the right time, with the right guidance. I had my father for 13 years. I had Bill more than three times longer.

I am blessed.

I am taking a page out of the Rona Maynard playbook. Please, if you have stories about being mentored or being a mentor, share! Let’s get this party started!

I remember how much he meant to you and your family. You were very fortunate to have him in your life. ❤️

Your sports experience reminds me of a DO story. I know it wasn't you, it was another Daily Orange editor-on who received a late call with headline instructions at the plant, and very reasonably set exactly what she was told – but not knowing sports, ended up with a headline about "Yukon Huskies" rather than "UConn Huskies." The sports guys, as I recall, took great umbrage at the next day's markup, whereas it seemed to me that *they* should have been more clear. But I took from that a permanent questioning of assumptions.