Thanks again for continuing to read What to Believe. As always, I love hearing what you think about the memoir and appreciate your spreading the word.

Chapter Nine

In late April, a family from central New York went canoeing not far from Kayuta Lake. Their canoe capsized and the divers who had been looking for my father were called away to look for them. I knew I should have felt sorry for the family’s survivors but I had no empathy. Who went canoeing when there was still snow on the ground? Why hadn't they been more careful? My father had been missing longer. What if his body turned up and no one was around to see it?

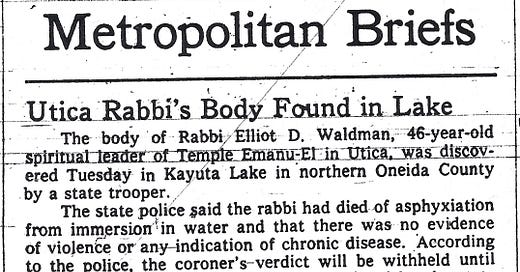

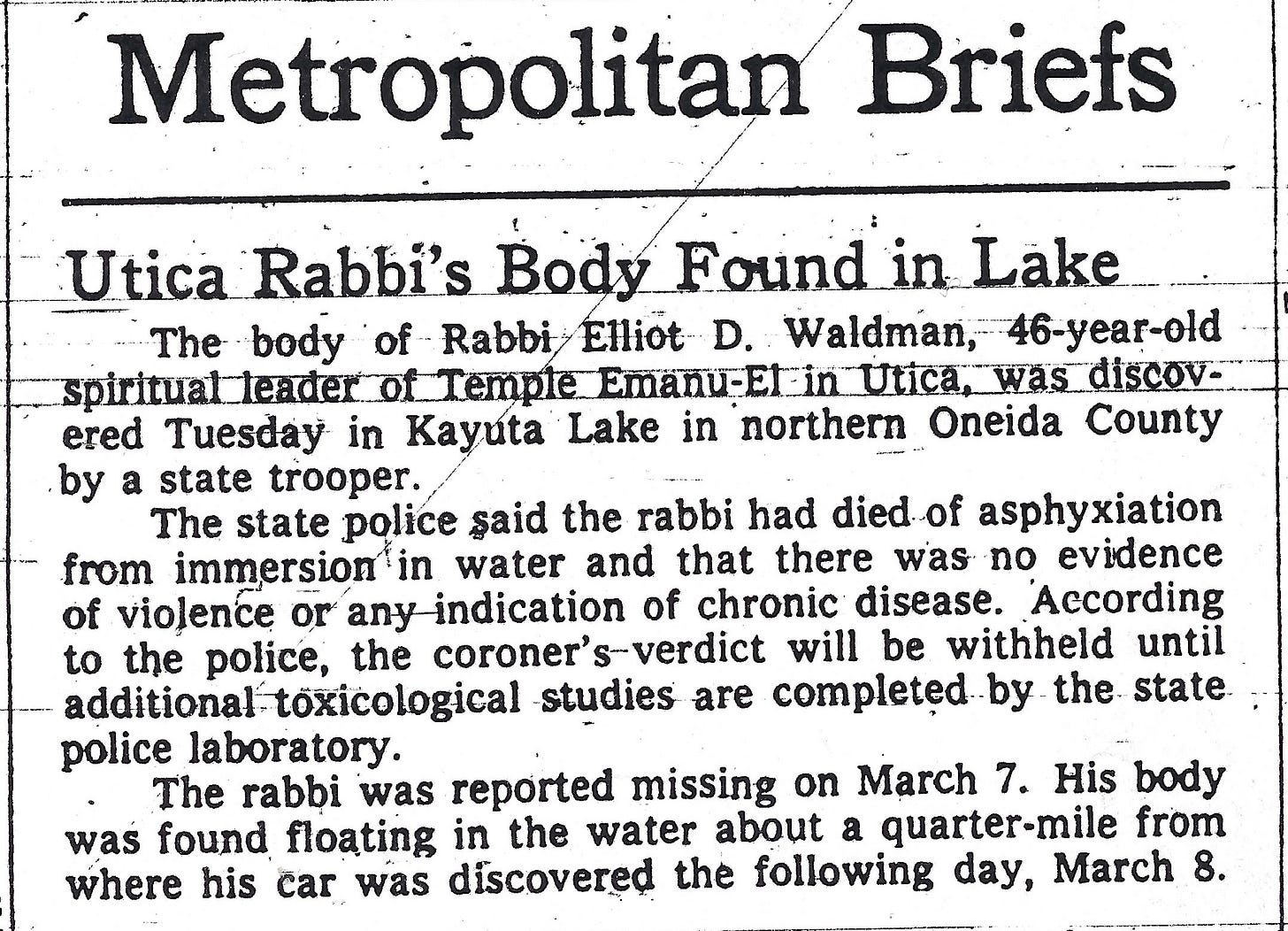

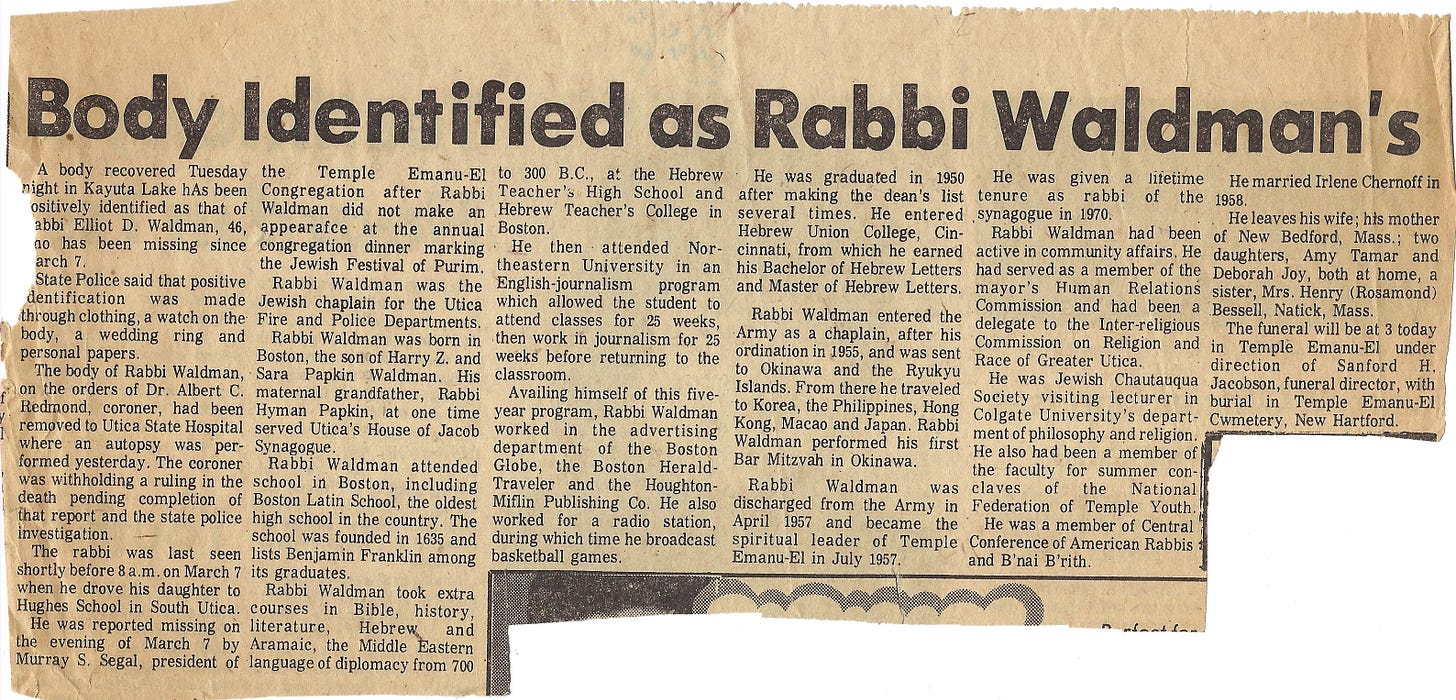

But when Dad’s body did turn up, someone was around to spot it on Tuesday evening, April 23, 1974, nearly seven weeks after he disappeared. That someone notified the State Troopers that a body was floating in the lake. The troopers retrieved it in a boat. The local media found out before we did.

Mom was entertaining that night. Some of her teacher friends had come over to show her how to make a new drink, a piña colada. They had coconut cream, pineapple juice, rum, and a blender. There was a lot of noise in the house, happy noise, which made me feel good, though I worried that my mother might get drunk. She didn't drink much and it seemed there was potential for overdoing it.

My sister was at school, rehearsing for "No No Nanette," the spring musical. She played cello in the pit orchestra. She was still at school when I went to sleep, and my mother and her friends were still in the living room drinking, talking, and laughing.

When I awoke the next morning I could tell by the light through my windows that I'd overslept. As I came down the stairs, my mother emerged from the kitchen and planted herself at the bottom landing, waiting for me. She was dressed, but not for school.

"Are you drunk?" I asked, the word “hangover” not a part of my vocabulary.

She didn't seem to have heard my question. "I have news for you," she said. Her voice was calm, betraying no emotion. Had I not known better, had this moment taken place on March 6, before everything changed for the worse, I might have guessed that her news was something on the order of “We’ve run out of Pop-Tarts, so you have to eat Corn Flakes for breakfast.”

But I knew what she was going to tell me, and I was neither scared nor surprised. I just wanted her to get it over with, so I saved her the trouble of having to form another sentence. "They found Dad, didn't they?" I said, throwing in the question at the end in an attempt to soften the statement.

She nodded.

"He's dead, isn't he?"

"Yes," she said.

I did not cry. Neither did she. Maybe she already had that day, though I do not recall thinking that her eyes looked red. As for me, I was past crying. I didn’t even feel choked up. This was the conversation I’d been anticipating since the second week in March. It was less news than confirmation, less a cause for grief than relief. The waiting was over. At last, we could get on with the business of living, whatever that was going to look like. Right now it looked like we weren’t going to school, the same as we hadn’t on March 8, but somewhere in the recesses of my mind I realized that the business of living would also include a funeral and that, owing to Jewish law, it could take place as soon as tomorrow.

"Does Amy know?"

"No," Mom replied. "I'm waiting for her to wake up."

"I'll tell her," I said. If my mother called after me to stop, I didn't hear. I continued up the stairs to Amy’s room, where I plopped myself down at the edge of her bed, shook her awake, and gave her the news.

Or at least that's how I remember it. Amy's recollection is different:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Debby's Substack: What to Believe to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.