The End

(A Good Thing)

For three weeks after Noah was discharged from the Adult Unit at Alberta Hospital Edmonton on May 31, 2008, he left sticky notes on our bedroom door every night summing up his day, and providing a numerical score for life and death. A good day was when “life” got a higher score than “death.” There were usually more good days than bad ones.

The sticky notes were a communication compromise: Noah had made it clear he didn’t want to sit down and discuss his feelings with us on a daily (or nightly) basis, and we’d made it clear we needed some way of knowing how he was feeling.

By June 17 he was ready to stop writing the notes. We told him we weren’t ready to stop receiving them, but a few days later we honored his wishes. He was right. It was time to move on.

A few weeks later, he wrote to the Registrar at the University of Alberta, asking to have his Winter 2018 semester wiped from his record and his tuition refunded. I warned him it was doubtful that he’d get the response he wanted — I’d asked one of the engineering deans if a refund was possible and he’d said no. But Noah was determined to try. He wanted to start with a clean slate.

The Registrar examined the supporting documents and spoke to Noah’s professors. Then she wiped the semester from his record and refunded his tuition. I was gobsmacked. It’s exactly what she should have done, but so often in this life, people don’t do the right thing. I wrote her a thank-you note.

Early that summer, Noah and I drove to Seattle to meet Dave at a conference. At lunch one day, he told me he was worried about going back to university, and when I asked what would make him feel better, he said, “Being dead.” I don’t remember how I responded — all I wrote in my journal was this:

And my heart started to sink and I did not know what to say, so for a bit I did not, but I also did not get all emotional because I felt that would be the wrong thing to do; I honestly felt a bit as if he was saying that to be hostile and I did not want to make things worse. And we talked more and I tried to stay calm and, well, I’ll write more later but suffice it to say the day seems to be ending well.

That was it. I didn’t write more later, or rather, I didn’t write more later about that. The day ended well because Noah went for a walk by himself, and he said he would be back in an hour, and he was. Whenever he went somewhere that summer and fall, he would tell us when he would be home and almost without fail, he would keep his word. If he was going to be late, he would let us know. The few times he failed to do that, I panicked until I heard from him, but I always heard from him.

In the fall of 2018, he returned to university to continue pursuing his civil engineering degree. Dave and I had encouraged him to take time off, but he was determined to finish with the classmates with whom he’d started the program. We warned him about the heavy course load. He assured us he could handle it. He was seeing a psychologist and taking meds. He began getting Bs for the first time in his university career and if it was bothering him, he didn’t let on.

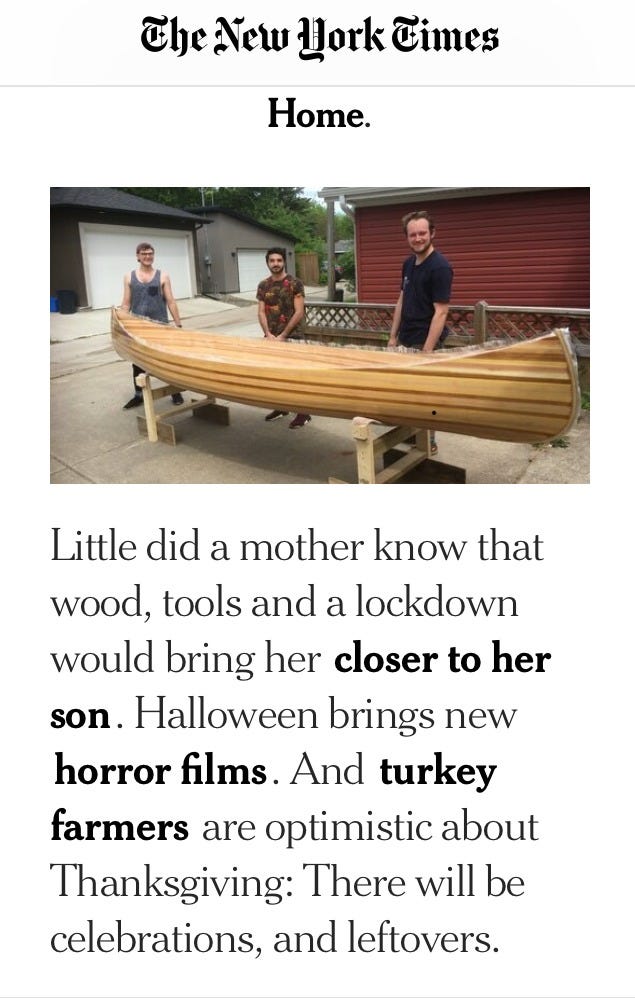

He graduated during the pandemic. When the start date for his job was delayed, he and his friends built a cedar strip canoe in our garage.

When the pandemic killed the job completely, he landed a position with a consulting firm, which provided him with the experience he needed to get a job a year and a half later as a transportation engineer. He earned his professional engineering designation a few months ago. He and his girlfriend — also a civil engineer — live 10 minutes from us. We see each other often. He helped us to organize a party on the weekend, and I was at his house last night helping make more than 100 potato latkes for him serve to his colleagues at a social event next week.

More than seven years have passed since Noah was a psychiatric patient. He still takes meds and sees a psychologist. He also reaches out to us regularly, sometimes to say hi or make plans to get together, sometimes for advice. He knows we’re here to support him in any way he needs. That’s one of the lasting, positive impacts of those difficult months: the lines of communication have remained open.

Another, the obvious: my son is alive and thriving.

I am blessed. I am grateful. I try hard to take nothing for granted.

Thank you for taking the time to read my story about Noah in the hospital. When I began serializing it a year ago, I wasn’t sure where or when I’d end it, and I’m not convinced that ending it here is going to satisfy everyone. But something I appreciate about Substack is that you can have a conversation with the writer. So if there’s more that you want to know, if you have questions or opinions, ask, or share. I will respond. I’m interested in your responses. I look forward to your feedback.

From now on, I’ll be sharing different kinds of stories: personal essays, essays about current events and books, and Q&As with interesting people. Next week I’ll publish my annual list of favorite books I’ve read during the past year.

As always, I want to acknowledge those of you who are willing and able to pay my $35-a-year subscription fee (and those of you who pay even more). I’m so grateful for all my readers. I hope you’ll continue to support my writing. It means the world to me.

I’ll close with a line from my friend and fellow Substacker, Rona Maynard: “Paid subscriptions are like rainbows.”

Thanks for the rainbows, readers. Here’s one I took on the Big Island of Hawaii in January 2009.

A happy ending. It was lovely to see him the other day, doing so well.

You have given many families hope. Thank you.